Overview

I. Summary

On November 13, 2025, the European Parliament adopted its negotiating position on the Commission's Omnibus package to streamline the EU's Sustainability frameworks, primarily the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D). Parliament's position is more pro-business than the Commission's proposal or the Council's position, since it further reduces the scope of obligations imposed on companies subject to both acts, and also limits the number of companies in the scope of the CSRD. While Parliament's position is only to set the stage for trilogue discussions in coming months, if adopted, the proposed amendments could have far-reaching practical implications for stakeholder rights and the design of corporate sustainability programs.

This post highlights some notable elements of Parliament's proposal and five implications for companies and stakeholders to track: (i) restrictions on requesting supplier information could make early risk identification more challenging; (ii) exceptions to the duty to suspend business relationships create such broad discretion that they may, in practice, swallow the rule; (iii) broad discretion in prioritization may significantly narrow the scope of sustainability programs and may make it difficult to hold companies liable for unaddressed harms; (iv) full harmonization of core due diligence duties precludes national regulators from seeking to overcome these limits; and (v) under the CSRD simplified, quantitative reporting and limited assurance will significantly streamline mandatory disclosure. While civil liability is no longer imposed, companies will still have to address potentially divergent civil liability regimes in different Member States.

As the CS3D continues to evolve, the legislative text inevitably departs further from certain elements of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights ("Guiding Principles"), underscoring the difficulty of translating soft-law human rights standards into binding rules. Regardless of the final contours of the CS3D, companies can expect persistent stakeholder pressure to maintain robust human rights programs, even where such expectations extend beyond the directive's binding obligations.

II. Omnibus Background

In February 2025, the European Commission published the Omnibus package, aiming to streamline the EU's corporate sustainability framework, particularly the CSRD and CS3D. The impetus was twofold: companies and member states raised concerns that the new sustainability obligations could impose heavy burdens and put EU companies at a disadvantage on the global market, and at the same time, political tensions emerged within Parliament and between Parliament and the Council over the ambition, timing and scope of these rules.

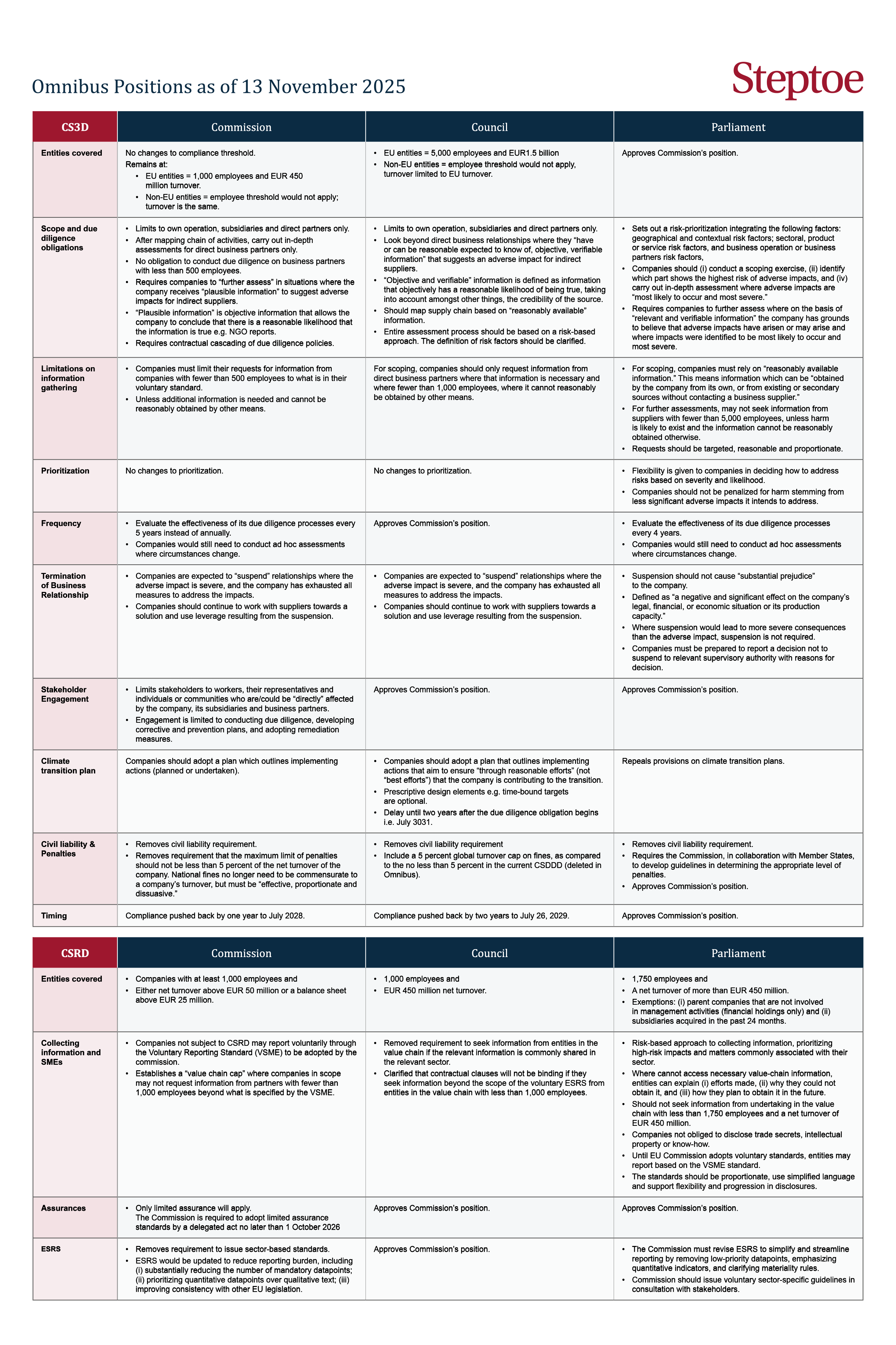

The Council published its General Approach to the Omnibus in June 2025, but Parliament has struggled to reach a consensus on its draft. The center-right parties pushed for higher thresholds and a more risk-based approach, while the Socialist & Democrats and Greens/EFA resisted what they saw as a dilution of the original directive's ambition. On 13 November 2025, Parliament adopted its much-anticipated negotiating position on the Omnibus, including the following key amendments to the Commission's proposed draft (we include a detailed table with the three positions as they stand at the end of this post):

CS3D

- Scope of due diligence obligations—it does not adopt the Commission's limitation to own operations, subsidiaries and direct partners only, but sets out a detailed risk-prioritization approach applying across the value chain. It also removes contractual cascading obligations, meaning companies are no longer required to impose due diligence requirements on lower-tier suppliers, many of whom are smaller operators.

- Structure—companies should adopt a risk-based approach to due diligence by first conducting a scoping exercise, without seeking information from business partners, and then conducting in-depth assessments where risks are most severe and likely to occur without seeking information from business partners with less than 5000 employees unless strictly necessary to obtain information needed.

- Prioritization—companies should address risks based on severity and likelihood of harm to stakeholders, but flexibility is afforded to them, and they should not be liable for harms resulting from risks they had deemed lower priority and intended to address after the higher priority risks.

- Suspension and termination of business relationships—where business partners do not address identified risks or adverse impacts, companies should seek temporary suspension before considering termination. But companies are not obliged to suspend relationships temporarily if there are no available alternatives, the partner provides an essential product or service, and suspension would cause "substantial prejudice" to the business.

- Creating a floor and a ceiling—prohibits member states from introducing in their national law provisions which differ from the substantive due diligence obligations in the CSDDD (Articles 6 to 16).

- Monitoring—evaluate the effectiveness of the due diligence approach every four years, instead of the Commission's proposed five years. Companies would still need to conduct ad hoc assessments to evaluate the effectiveness of its due diligence processes where circumstances change.

CSRD

- Scope—raises the threshold for determining the scope of the CSRD to companies with more than 1,750 employees and a net turnover above EUR 450 million. It exempts (i) parent companies that are not involved in management activities (financial holdings only) and (ii) reporting on subsidiaries acquired in the past 24 months.

- Collecting information—establishes a risk-based approach to collecting information, prioritizing high-risk impacts and matters commonly associated with their sectors; allows companies to explain where they cannot access necessary information.

- Reporting simplifications —requires the Commission to streamline the ESRS by removing low-priority datapoints, prioritizing quantitative indicators and clarifying materiality rules, and to develop voluntary sector-specific guidelines. Until voluntary SME standards are issued, companies may rely on EFRAG's VSME standard, and in-scope companies should not request information from value-chain partners below the 1,750-employee / EUR 450m turnover threshold beyond what the VSME requires.

- Limited assurance—endorses the Commission's position to remove reasonable assurance and emphasizes that the Commission should adopt a delegated act urgently to adopt harmonized assurance.

The text now proceeds to trilogue negotiations between Parliament, Council, and the Commission, where it is expected that the Council will largely endorse Parliament's position. The EU hopes to finalize negotiations by the end of 2025, though reaching this deadline is uncertain due to some of the key differences among the co-legislators on some of the core issues above.

1. Practical Implications

Below we highlight five key implications from Parliament's amendments, and what they mean in practice, for global companies:

2. Restrictions on supplier information could weaken effective risk management

One of the most significant changes introduced by Parliament is tighter restrictions on companies' ability to request information from business partners through CS3D due diligence. At the scoping stage, companies should "not seek to obtain information from business partners but rely on information that is already reasonably available, such as public information, information from searches and information gained through earlier cooperation" (amendment 22). At the in-depth assessment stage, companies should only obtain information from business partners where it is "necessary in light of indications of likely adverse impacts," (amendment 22). Where the business partner has fewer than 5000 employees, companies may "seek such information only as a last resort, and if it cannot reasonably be obtained by other means…in any case, any request shall be targeted, reasonable and proportionate" (amendment 91).

These parameters shape how companies will be able to identify and assess risks across their value chain. Publicly available resources, such as media reports and NGO publications, can help orient scoping and risk identification, but they are often incomplete, outdated or too general to capture supplier-specific issues. This presents a particular challenge because, for most global companies, the most salient human rights and environmental risks lie precisely at the level of small suppliers beyond tier 1. It is important to note that companies can still request information from those suppliers, either as part of their human rights programs or in connection with other laws, such as the EU's Forced Labor or Deforestation Regulations. They just will not be penalized under the CSDDD if they fail to do so, and a relevant negative impact arises.

3. Exceptions to termination of business-relationships duty will likely swallow the rule

Parliament's amendments to the CS3D significantly narrow the circumstances in which companies should suspend a business relationship after identifying a severe adverse impact. Parliament highlights that suspending a business relationship should be "temporary," and done after an assessment is conducted in consultation with relevant stakeholders to determine whether (i) no "available alternative" to that business relationship exists; (ii) the suspension would "cause substantial prejudice to the company" (amendment 24); or (iii) whether the adverse impacts from suspension can be "manifestly more severe" than the adverse impact that could not be addressed effectively (amendment 96).

These concepts generally track the "crucial relationship" considerations in Guiding Principle 19, which recognizes that ending a relationship may not be feasible where the supplier provides a product or service essential to the company's operations and no reasonable alternative exists. Under the Guiding Principles, companies may remain in such relationships provided they actively work to mitigate the impact and accept the consequences of continued linkage. Parliament's amendments reflect a similar logic but introduce broad discretion in determining when suspension is required, creating multiple avenues for companies to justify a continued relationship even where serious adverse impacts persist. As a result, the discretion is wide enough that it may, in practice, risk swallowing the rule. The amendment also raises questions about how temporary suspension would function in practice. In complex value chains, even a temporary halt may have effects not unlike termination, particularly where production schedules, logistics chains, or multi-tier dependencies make it difficult to halt or restart the relationship without substantial costs. It remains unclear how regulators will expect companies to weigh such operational uncertainty against the duty to address severe impacts, and the extent to which companies will with to continue engaging with business partners associated with significant negative impacts.

4. Broad discretion in prioritization will shift how companies address risks

Parliament's amendments introduce an explicit prioritization mechanism that allows companies broad discretion to address the most salient adverse impacts first. "Companies should be given significant flexibility in deciding which risks to address first on the basis of the severity and likelihood of an adverse impact. Such a decision should be based on the scale, scope or irremediable character of the adverse impact, taking into account the gravity of the impact. … [C]ompanies should not be penalized for any harm stemming from less significant adverse impacts that were not yet addressed according to the prioritization in line with these principles."

The amendment's reference to "significant flexibility"—particularly when combined with the inherent discretion in prioritization criteria and lack of specificity regarding number of priorities—effectively creates a variant of the business judgement rule, offering corporate leaders substantial deference in how they design and implement sustainability due diligence. As a result, the safe harbor for unaddressed "less significant" impacts may prove extremely broad in practice. It is important to note that companies could, of course, still face accountability under other laws and regulations.

5. Full harmonizations of core duties limits national divergence—but companies' ability to exceed them is uncertain

Parliament expands the scope of the harmonization clause, stating that "member states shall not introduce, in their national law, provisions within the field covered by this Directive diverging from those laid down in Articles 6 to 16" (amendment 85). This means that the CS3D will set both floor and ceiling for EU member states' national regulation on sustainability due diligence. The provisions thus significantly limits the risk of divergent national laws, which might otherwise complicate program design and implementation. For stakeholders, however, the preset ceiling may create significant frustration, because the effect of the other proposed amendments is to substantially limit sustainability-related obligations and potential liability.

6. Streamlining of reporting obligations

To streamline sustainability reporting, Parliament requires the Commission to issue a delegated act—within six months of the directive taking effect—updating the ESRS to make them simpler and more focused. This includes "removing datapoints deemed least important for the general purpose of sustainability reporting" and "prioritizing quantitative indicators over narrative text" (amendment 10). Parliament has also endorsed limited assurance, which would significantly reduce the document-intensity, time, and cost of preparing sustainability disclosure. The proposal will be welcomed by many, as preparing sustainability disclosure assured according to nebulous standards risked consuming sustainability due diligence.