Overview

Over the past several years, litigation over the chemicals known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) has been growing both in scope and complexity. This article provides a basic overview of PFAS litigation, focusing primarily on environmental litigation (both in the United States and the European Union) as well as consumer products litigation (in the United States), and offering insights on what the cases typically look like, lessons learned, and the road ahead.

I. What are PFAS

PFAS are a large complex group of synthetic (i.e., man-made, rather than naturally occurring) chemicals that have been used in various consumer and industrial applications since the 1950’s. To provide just a few examples, PFAS have been used in nonstick cookware, water-resistant clothing, stain-resistant carpeting, and firefighting foam. At a basic level, PFAS molecules comprise a chain of carbon atoms linked to fluorine atoms. The carbon-fluorine bond, one of the strongest in nature, facilitates the many beneficial uses of PFAS but also makes PFAS slow to degrade in the environment, earning PFAS the moniker "forever chemicals."1 While the science on the effects of PFAS is still developing, plaintiffs typically assert that PFAS are slow to degrade, bioaccumulate (build-up) in the body, impact humans through multiple exposure pathways (e.g., air, drinking water, food packaging), and cause negative health effects. It is important to note, however, that the thousands of different chemicals under the PFAS umbrella do not all behave in the same way, so treating this entire group as a monolith is both scientifically and conceptually unsound.

II. PFAS Litigation Trends

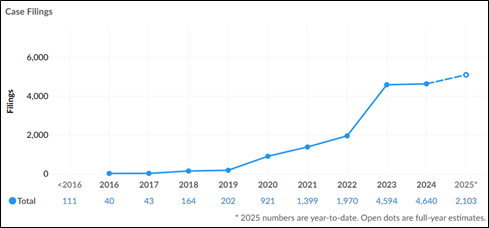

PFAS litigation has expanded significantly in recent years. A search of public federal court filings in the US referencing PFAS shows the following trend2:

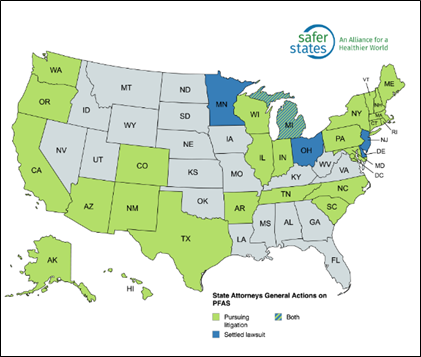

As of December 2024, the Attorneys General of 30 states and DC have initiated litigation against the manufacturers of PFAS chemicals for contaminating water supplies and other natural resources.3

Last year alone, 3M announced settlements for $10.3 billion (payable over 13 years), to settle with certain public water systems as a result of alleged PFAS contamination in drinking water (discussed further below).4 DuPont (and related entities) similarly announced settlements for nearly $1.2 billion in 2023 (funded in full and deposited with the court following preliminary judicial settlement approval) to resolve PFAS claims by the public water systems.5 In May of 2025, 3M announced a settlement (subject to court approval) with the State of New Jersey for up to $450 million ($285 million to be paid this year, with additional payments over the next 25 years), to resolve PFAS claims.6 DuPont (and its spinoff company) are currently in the middle of a landmark multi-phase trial against the State of New Jersey over their use of PFAS chemicals at the Chambers Works manufacturing plant and the alleged resulting environmental exposure.7

PFAS litigation is not limited to environmental exposure or drinking water contamination. The State of Texas, for example, recently sued PFAS manufacturers for falsely advertising PFAS-containing household products as being safe for families.8And the plaintiffs' bar has taken the fight to consumer products, suing multiple technology companies for allegedly having PFAS in wearable products, suing food and beverage companies for PFAS allegedly found in packaging, and suing pharmaceutical companies for PFAS found in bandages, among many others. In short, PFAS litigation is growing both in terms of the number of lawsuits filed, the types of plaintiffs bringing the suits, and the number of industries impacted.

III. PFAS Environmental Litigation

A. United States

In the United States, a typical PFAS environmental litigation timeline looks like any other complex case: a complaint is filed, followed by an answer or a motion to dismiss, fact discovery, expert discovery, Daubert and summary judgment motions, then pre-trial motions, trial, and possibly appeal. A few things, however, make PFAS litigation unique. For example, (1) depending upon the jurisdiction and court, there may be a low bar for plaintiffs to assert claims, (2) there are high costs to defend the suits, as often there is no mechanism to challenge the science behind plaintiffs’ assertions until completion of expert discovery, (3) the standards of PFAS testing and detection are still being developed, (4) as noted above, PFAS chemistries are not all the same, though plaintiffs often attempt to treat them as such to their advantage, and (5) most judges are less familiar with PFAS matters than the more typical cases on their dockets.

In environmental cases, the plaintiffs can include individuals, putative class representatives, water companies, and state and local governments. The claims that are typically asserted include negligence or gross negligence, private and public nuisance, trespass, strict liability (failure to warn, abnormally dangerous activity, or design defect), and violation of state and federal environmental laws. Defendants can include not only manufacturers of PFAS but also companies that utilize PFAS in their operations or activities. While some defenses (e.g., lack of standing or statute of limitations) can be asserted at the pre-discovery phase on a motion to dismiss, the strongest defenses (e.g., lack of causation) are often heavily dependent on expert discovery and cannot be introduced until months or even years into the case.

The damages the plaintiffs seek also vary. For example, a state government may attempt to seek damages for remediation/cleanup costs or damages to natural resources. A town may attempt to seek the costs to cover the installation of industrial filters to filter out PFAS from the municipal water supply. Individuals can attempt to seek damages for costs of purchasing personal filters or bottled water, or damages for diminution of property values. Individuals with personal injuries allegedly caused by PFAS may attempt to seek damages typically associated with personal injury claims. Perhaps the most unique form of damages comes in the form of "medical monitoring." These are damages sought by individuals exposed to PFAS, who are currently perfectly healthy, but allege that they are at an "increased risk" of developing certain diseases in the future due to their present PFAS exposure. Thus, they seek to have defendants pay for monitoring (usually in the form of specific medical exams) for some period of time in the future. Notably, different states have taken different approaches to medical monitoring, and there is no uniformity on: (1) whether medical monitoring is even recognized, (2) whether a plaintiff can seek medical monitoring without a present personal injury, (3) whether medical monitoring is a cause of action or a measure of damages accompanying a separate cause of action, (4) the elements that a plaintiff is required to demonstrate to obtain medical monitoring, (5) whether—and this is particularly significant for certification of class action lawsuits—medical monitoring is considered to be "injunctive" or "declaratory" relief (as in the case of a court-supervised monitoring program), or (6) whether it can constitute a simple payment of money to plaintiffs who can then use the funds for future testing (which would likely not be considered to be "injunctive" or "declaratory" relief, making a different provision of the class certification rule come into play).9

Of particular note in the environmental litigation landscape, in 2018, the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation consolidated cases involving PFAS in aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF) in a multidistrict litigation (MDL) in the District of South Carolina before Judge Richard Gergel. The MDL comprises thousands of cases, including claims by public water providers seeking drinking water testing and remediation costs (many of these have reached settlements referenced at the beginning of this article), individuals seeking personal injury claims and medical monitoring, property owners seeking remediation and cleanup costs for contamination, and states seeking natural resource damages.10 In 2024, Judge Gergel selected plaintiffs with certain personal injuries for bellwether trials, with the first trial date set for October 2025.11

B. European Union

PFAS environmental litigation is not limited to the US, and large-scale environmental cases have been filed in the EU. For example, the collective Darkwater 3M, together with 1,400 local residents living near the 3M Zwijndrecht plant in Antwerp, filed a class action against 3M in 2024. These actions can be cross-jurisdiction in nature: in 2023, a collective of Dutch fishermen, and also the Dutch government, took aim against 3M for allegedly polluting the Western Scheldt river from 3M's plant in Belgium. Defendants include PFAS manufacturers, governments, and AFFF users, but also water treaters or suppliers.12For example, in a landmark case, the Supreme Court of Sweden declared that elevated levels of PFAS in the bloodstream is in principle an injury under EU product liability rules.13 EU PFAS litigation differs in some ways from litigation in the US: (1) litigation standards are not harmonized across the EU; there are 27 independent legal regimes with their own court systems, bar admissions, language, and legal standards, (2) not all EU Member States allow for collective/representative actions (like class actions in the US), (3) the joinder of cases is also typically limited (unlike the MDL process in the US), (4) the discovery tools are different and access to evidence is generally more restricted, (5) there is a less litigation-focused culture, and (6) the use of third-party litigation funding is currently much more limited though expected to play a growing role in the future. Nevertheless, as in the US, there is an increased regulatory and litigation focus over PFAS chemicals in the EU.

IV. PFAS Consumer Products Litigation

As noted above, beyond environmental litigation, consumer cases are becoming increasingly frequent in the US. These cases often originate from "independent testing" (though plaintiffs' firms often have relationships with the testing laboratories) revealing the presence of PFAS in a consumer product. The plaintiffs' bar also monitors publications, such as Consumer Reports or RetailerReportCard, which reveal testing results for consumer products. Plaintiffs in these cases typically allege that the companies are making false representations (e.g., stating their products are "all natural," "healthy," or "clean"), or omissions (that companies should have disclosed that their products contained PFAS, but failed to do so). Typically, consumers allege something along the lines of "I would not have purchased this product or would not have paid as much as I did, had I known that it had PFAS in it." Consumers seek damages that include, for example, price premiums (the difference between what the consumer paid and what the product is allegedly worth), restitution (return of the price paid), disgorgement (return of profits retained), and statutory damages (which vary by state). They may also seek injunctions, barring defendants from advertising their products as "natural," until the PFAS chemicals are removed. Often, the suits are brought as putative class actions, with the named plaintiff seeking to represent all purchasers of the product at issue in a particular state, or even all purchasers in the US, over the period of time covered by the statute of limitations.

Defendants in consumer products suits may overlap with, but are somewhat different from, those in the environmental suits discussed above, and may include manufacturers, retailers, restaurant brands, raw materials suppliers, or packaging suppliers. The entity whose name is on the package or on the advertising is the one most often named, though retailers are named if the product is a store brand, and the plaintiff wants to put pressure on the manufacturer. Typical defense themes in these cases include the idea that one cannot extrapolate from a single test of an exemplar product to the product line as a whole. Defendants typically argue that the actual product plaintiff purchased was not tested, and therefore there is no evidence that the plaintiff’s product actually contained PFAS. They may also argue that PFAS was not intentionally added to the product, that trace PFAS levels are unavoidable, and that "testing" does not show the presence of contamination at a level that exceeds a risk-based threshold. Because the health impacts of exposure to trace levels of PFAS are uncertain or unknown, defendants often argue that allowing a plaintiff to sue on behalf of a large class of purchasers, based on nothing more than the potential that a product may contain trace levels of PFAS, could lead to the courts opening the 'floodgates' to huge numbers of speculative claims.

Unlike the environmental cases discussed above, the consumer cases may be more frequently resolved on a motion to dismiss, based on the arguments above, though this depends on the law of relevant jurisdictions, as the defense arguments noted above have been accepted by some jurisdictions but rejected by others. The class action nature of these claims often puts pressure on defendants to settle because, while an individual plaintiff’s claim may only be worth a few dollars, the claims of every purchaser in a given state for a period of three or four years (the statute of limitations period) could add up to many millions. For this reason, in consumer cases, there are likely many pre-suit demands that are quietly settled before a complaint is filed and becomes public information.

Thus, defendants in consumer cases are often faced with a choice between two strategies: (1) quietly settle the case at the complaint (or demand letter) stage, or (2) vigorously defend the case at every stage (e.g., file an aggressive motion to dismiss and aggressive discovery, fight class certification, and appeal negative rulings). The former, while quickly disposing of a case, offers no protection from copy-cat suits, and may turn settlement into a never-ending game of "whack-a-mole." The latter, while sending a stronger signal, may inadvertently attract copy-cat suits due to increased case publicity. The right strategy will depend on the facts of the case and the jurisdiction where the case is (or likely will be) brought, as well as a defendant company’s long-term business plans concerning the product line at issue.

V. Conclusions and Steps You Can Take Now

PFAS litigation is not going away. So, what steps can companies take to protect themselves now? In the area of environmental suits, companies should consider (1) reviewing company history and potential usage of PFAS (though realizing that the chemicals may not have been called "PFAS" at the time), (2) assessing firefighting systems historically and currently on site, as well as history of fires and potential AFFF usage, (3) analyzing potential nearby sources (e.g., airports, military bases, firefighter training facilities, rail accidents, rivers), and (4) paying attention to local and state regulations that are not immediately obvious (e.g., real estate law requirements for sellers to disclose PFAS contamination). In the area of consumer product suits, companies should consider: (1) phasing out PFAS usage in their products, (2) reviewing their advertising statements, (3) testing their products for the presence of PFAS (with assistance from counsel, to provide work-product protections), and (4) reviewing their supply chain contracts for indemnification clauses, as well as their insurance policies.

Steptoe LLP is available to help clients navigate these issues both in the United States and the European Union.

1 See generally: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/pfc#:~:text=They%20are%20ingredients%20in%20various,linked%20carbon%20and%20fluorine%20atoms

2 https://law.lexmachina.com/ (search "PFAS")

3 https://www.saferstates.org/priorities/pfas/?section=state-ags-pfas-action

4 https://investors.3m.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/1836/3m-settlement-with-public-water-suppliers-to-address-pfas

5 https://www.dupont.com/news/chemours-dupont-and-corteva-reach-comprehensive-pfas-settlement-with-us-water-systems.html

6 https://investors.3m.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/1887/3m-resolves-pfas-related-claims-with-the-state-of-new-jersey; https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/13/climate/3m-pfas-forever-chemical-lawsuit-water-new-jersey.html; https://www.nbcphiladelphia.com/investigators/3m-forever-chemicals-settlement/4184776/

7 https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2025/05/landmark-forever-chemical-pollution-trial-south-jersey-dupont-chemours/

8 https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/news/releases/attorney-general-ken-paxton-sues-manufacturers-toxic-pfas-forever-chemicals-falsely-advertising

9 See, e.g., Barnes v. Am. Tobacco Co., 161 F.3d 127 (3d Cir. 1998)

10 See In Re: Aqueous Film-Forming Foams Products Liability Litigation, MDL No. 2:18-mn-2873

11 See Id. at Docs. 5361, 6544, 7094. A bellwether trial is a test case the outcome of which is expected to help guide the resolution of additional similar cases and inform settlement negotiations. The term "bellwether" comes from old shepherding practices: "Since long ago, it has been common practice for shepherds to hang a bell around the neck of one sheep in their flock, thereby designating it the lead sheep. This animal was historically called the bellwether, a word formed by a combination of the Middle English words belle (meaning 'bell') and wether (a noun that refers to a male sheep . . .). It eventually followed that bellwether would come to refer to someone who takes initiative or who actively establishes a trend that is taken up by others." (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bellwether)

12 See generally: https://www.brusselstimes.com/1006931/500-times-more-pfas-in-blood-of-3m-worker-than-eu-standard-allows; https://thefishingdaily.com/latest-news/pfas-contamination-in-western-scheldt-sparks-legal-action-by-fishing-groups/; https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/dutch-government-hold-3m-liable-forever-chemicals-damage-2023-05-23/; https://www.dutchnews.nl/2024/04/government-faces-legal-action-over-forever-chemical-failings/

13 https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2024-03-06/sweden-supreme-court-declares-high-levels-of-pfas-in-blood-constitutes-personal-injury/