Overview

Introduction

The jury has spoken, and the verdict is in. After days or weeks of presenting evidence, examining witnesses, and advocating for your client, the trial phase may be over—but the case is not. Whether you prevailed and need to protect the judgment, or you came up short and are evaluating avenues to challenge the result, the period immediately following trial is often one of the most consequential stages of the litigation.

For the prevailing party, post‑trial motions are an opportunity to preserve the verdict, correct technical issues in the judgment, and ensure the record supports enforcement and appeal. For the losing party, those same motions may provide a critical chance to address legal or factual errors, preserve appellate complaints, or—in some cases—obtain meaningful relief from the trial court itself. In either posture, strategic post‑trial motion practice can shape what happens next, in both the trial court and on appeal. Indeed, in addition to serving their purpose in the trial court, post-trial motions are vital appellate tools that can lay the groundwork for a successful appeal.

Post‑trial motions are not glamorous, and they are often complex. They may require counsel to act quickly, marshal a complete trial record, and persuade a judge—often the same one who presided over trial—that further action is warranted. Yet giving this stage of litigation the short shrift can jeopardize hard‑won victories or permanently waive viable challenges to an adverse outcome.

This article defines the most common post‑trial motions and offers practical tips for approaching them with purpose. These strategies are designed to help you navigate post‑trial motion practice with clarity, precision, and confidence regardless of whether you are seeking to hold onto a favorable verdict or undo an unfavorable one.

Post-Trial Motions

Post-trial motions are formal requests made after the verdict or judgment, asking the trial court to preserve the verdict or revisit aspects of the case. These motions typically address alleged prejudicial errors, newly discovered evidence, or other grounds that may justify altering the judgment or ordering a new trial. They are not necessarily about arguing that the jury got it wrong; instead, they often involve strategically pointing out legal or factual mistakes that affected the fairness of the trial. Unlike appeals, post-trial motions are filed in the same court in which the original trial occurred to give the judge one last chance to correct errors before the case moves on.

Post-trial motions and the arguments they present come in a variety of forms. For example, in a complex commercial dispute, a party might argue that during trial it established a defense of ratification as a matter of law and therefore its opponent should take nothing on its breach of fiduciary duty claims. Or perhaps in a high‑stakes products‑liability action, the argument is that a $150 million punitive damages award was excessive and unconstitutional given that there was no evidence that the defendant knowingly sold a cancer-causing herbicide, or that one of the jurors made discriminatory comments throughout the trial.

Whatever the reason, post-trial motions generally aim for one of three outcomes:

- Set aside the verdict and enter judgment for the moving party based on errors at trial;

- Adjust damages by reducing an excessive award or increasing an insufficient one based on the evidence; or

- Order a new trial due to errors that can be remedied only by starting fresh.

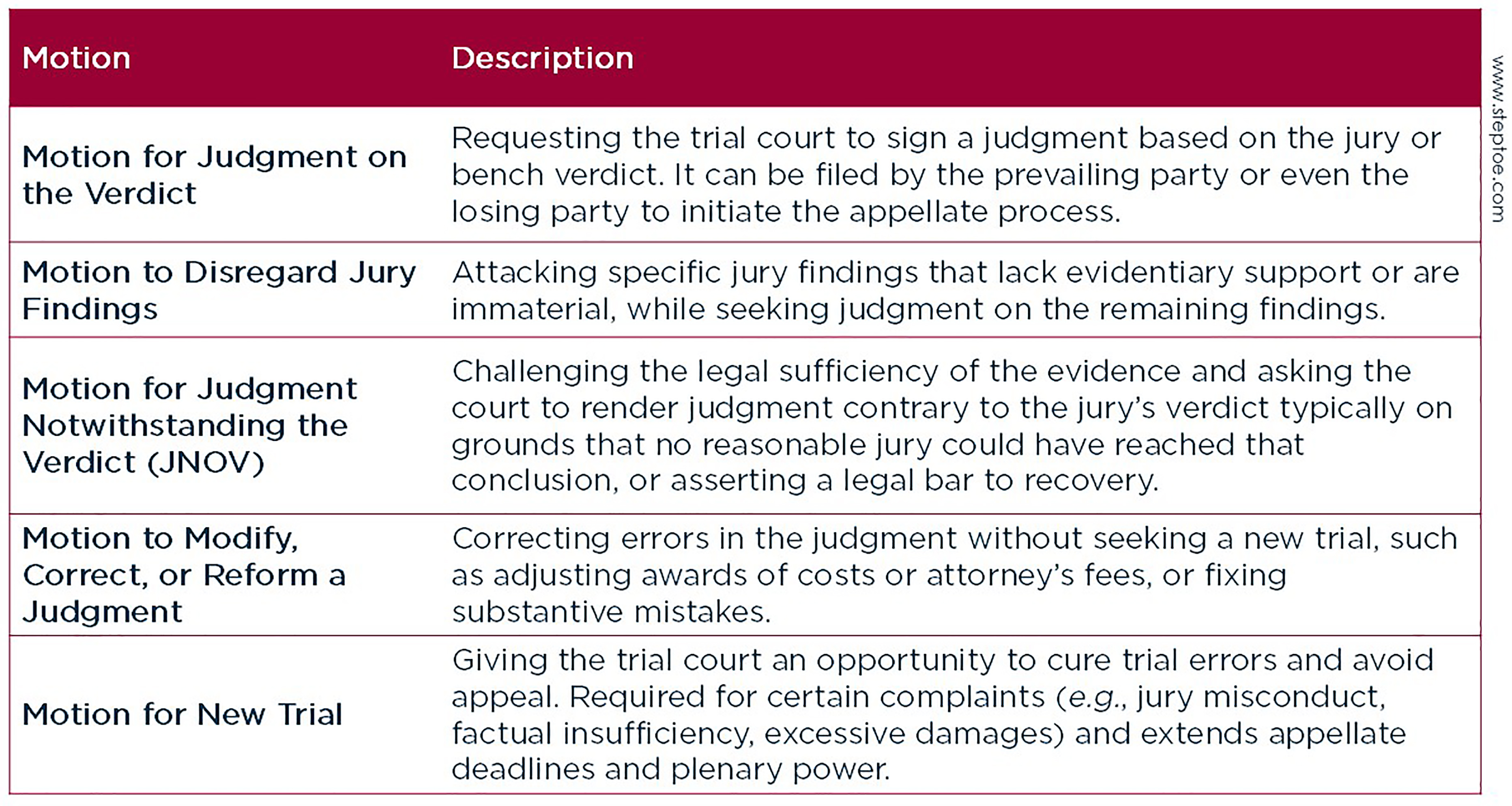

To achieve these objectives, parties have a range of options, each tailored to a specific purpose. The chart below summarizes the most common post-trial motions and their purposes:

Post-Trial Motion Practice Tips

1. Challenge errors with the appropriate motion.

The first step in seeking to undo a verdict or correct an error that occurred during a trial is choosing the right vehicle for your motion. For example, in Texas and in many other jurisdictions, a party must present its arguments to the trial court in a motion for new trial to preserve a factual sufficiency challenge for appeal. See Tex. R. Civ. P. 324(b)(2), (3); see also Dupree v. Younger, 598 U.S. 729, 731 (2023) (explaining that in federal court "a party who wants to preserve a sufficiency challenge for review on appeal must raise it anew in a post-trial motion"). A movant challenges the evidence supporting a jury finding as factually insufficient if she did not have the burden of proof during trial. See Raw Hide Oil & Gas, Inc. v. Maxus Exploration Co., 766 S.W.2d 264, 275–76 (Tex. App.—Amarillo 1988, writ denied). If the movant had the burden of proof, then the factual sufficiency challenge is couched as the jury's finding being "against the great weight" of the evidence. Id. While parties can also assert a legal (as opposed to a factual) insufficiency challenge in a motion for new trial, it is not optimal given that the remedy is a remand for a new trial and not rendition of judgment. See El-Khoury v. Kheir, 241 S.W.3d 82, 90 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 2007, pet. denied). Hence, legal sufficiency issues are better suited for a motion for instructed verdict, motion for JNOV, objection to the charge, or motion to disregard a jury's finding. See Steves Sash & Door Co. v. Ceco Corp., 751 S.W.2d 473, 477 (Tex. 1988). Failing to use the correct motion or omitting specific grounds can waive review altogether.

2. Use qualifying language to avoid waiver.

After the trial, a party that desires to initiate the appellate process may file a motion for judgment on the verdict for the trial court to sign. It is important to note that moving for judgment on the verdict can inadvertently waive appellate arguments if the movant does not specifically reserve the right to challenge the judgment. Without this qualifying language, the movant can give the appearance that it embraces the substance of the judgment.

To preserve the right to contest on appeal, the movant should state in the motion for judgment that it: (1) agrees only to form; (2) expressly disagrees with the content and result; (3) reserves the right to appeal; and (4) preserves sufficiency challenges. This can be in the form of a clause similar to the following:

While Plaintiffs disagree with the findings of the jury and feel there is a fatal defect which will support a new trial, in the event the Court is not inclined to grant a new trial prior to the entry of judgment, Plaintiffs pray the Court enter the following judgment. Plaintiffs agree only as to the form of the judgment but disagree and should not be construed as concurring with the content and result.

See, e.g., First Nat'l Bank v. Fojtik, 775 S.W.2d 632, 633 (Tex. 1989). While courts vary on the extent of waiver, the best practice is to expressly preserve the movant's ability to attack the judgment on appeal. Even if your case is in a jurisdiction that does not categorize the lack of express preservation as waiver, adding similar language serves as a belt-and-suspenders approach to the record—a small effort for significant protection.

3. Understand which post-trial motions extend appellate deadlines and which do not.

When preparing a post‑trial motion, the drafter should consider not only persuading the trial court to correct or refine its judgment, but also building a clean, complete record that positions the case for success on appeal. Lawyers who treat post‑trial motions as both advocacy and preservation tools are far less likely to confront waiver traps, missed deadlines, or gaps in the evidentiary record that can doom appellate issues.

Part of maximizing successful preservation of issues includes involving specialized appellate counsel throughout both the trial and post-trial motion stage. Having a trusted colleague or appellate counsel review and advise on any post-trial motions can provide a fresh perspective on which issues are strong for appeal and how to catch errors. Furthermore, this collaborative process helps frame the legal issues to tell a compelling story on appeal, ensuring that the narrative presented to the higher court is both legally sound and persuasively structured from the outset.

Appellate counsel can also assist in reviewing your jurisdiction's preservation rules to maximize an issue's chance of future appellate review. Certain motions— such as a timely filed motion for new trial or a motion to modify, correct, or reform the judgment (when seeking a substantive change)—will generally extend both the trial court's plenary power and the deadline to file a notice of appeal. By contrast, motions to disregard jury findings or for judgment on the verdict do not necessarily extend appellate deadlines or plenary power. In some jurisdictions, including Texas, a motion for JNOV is not listed in the appellate rules as extending deadlines, but courts often treat it as doing so if filed within 30 days and seeks a substantive change of the judgment. See, e.g., Kirschberg v. Lowe, 974 S.W.2d 844, 848 (Tex. App.—San Antonio 1998, no pet.). Finally, clerical-only corrections do not toll appellate deadlines. See, e.g., Lane Bank Equip. Co. v. Smith Southern Equip., Inc., 10 S.W.3d 308, 313 (Tex. 2000) (explaining that by filing a motion to correct a discrepancy between the written judgment and the judgment as pronounced by the court, such as a motion for judgment nunc pro tunc, the filing party does not extend the plenary power of the court or the appellate deadlines because it does not seek a substantive change in the judgment). Knowing these distinctions ensures you pair the proper motion with your preservation strategy and avoid losing appellate rights by operation of law.

4. Write for a busy trial judge.

Post-trial motions compete for attention in busy trial judges' crowded dockets. Thus, get right to the point and state the purpose of the motion at the outset. Avoid wasting the opening paragraph on party names or procedural history. Instead, start with a bold, punchy synopsis of the relief you are seeking and why. Consider separating each request into bullet points, which will make the introduction more readable and easier to digest. This approach gives the judge immediate clarity and sets the tone for the rest of the motion.

Equally important is organization and candor. Begin with the strongest ground for relief. Use short, bold headings like "Background," "Authority," and "Argument" so the judge can navigate quickly. Break complex points into numbered or bulleted lists to make them digestible and never sacrifice credibility. Ensure that every statement is one that can be cited from the record. Judges value clarity and directness, so structure your motion for simple reading and maintain transparency throughout. These techniques do not just improve readability, they enhance persuasion.

Conclusion

While often overlooked and lacking the sensational impact of jury verdicts, post-trial motions play a crucial role in the judicial process. They ensure that trials adhere to legal standards and that justice is served. Post-trial motions can also make or break an appeal, and they are often the difference between having one's arguments heard by an appellate court and watching them disappear due to waiver. The rules governing these motions vary across jurisdictions, but the underlying principles remain the same: precision, timing, and strategy, coupled with the vital tasks of preserving a clean record for appeal and affording the trial court a final opportunity to correct errors before the case moves forward.