Overview

Overview

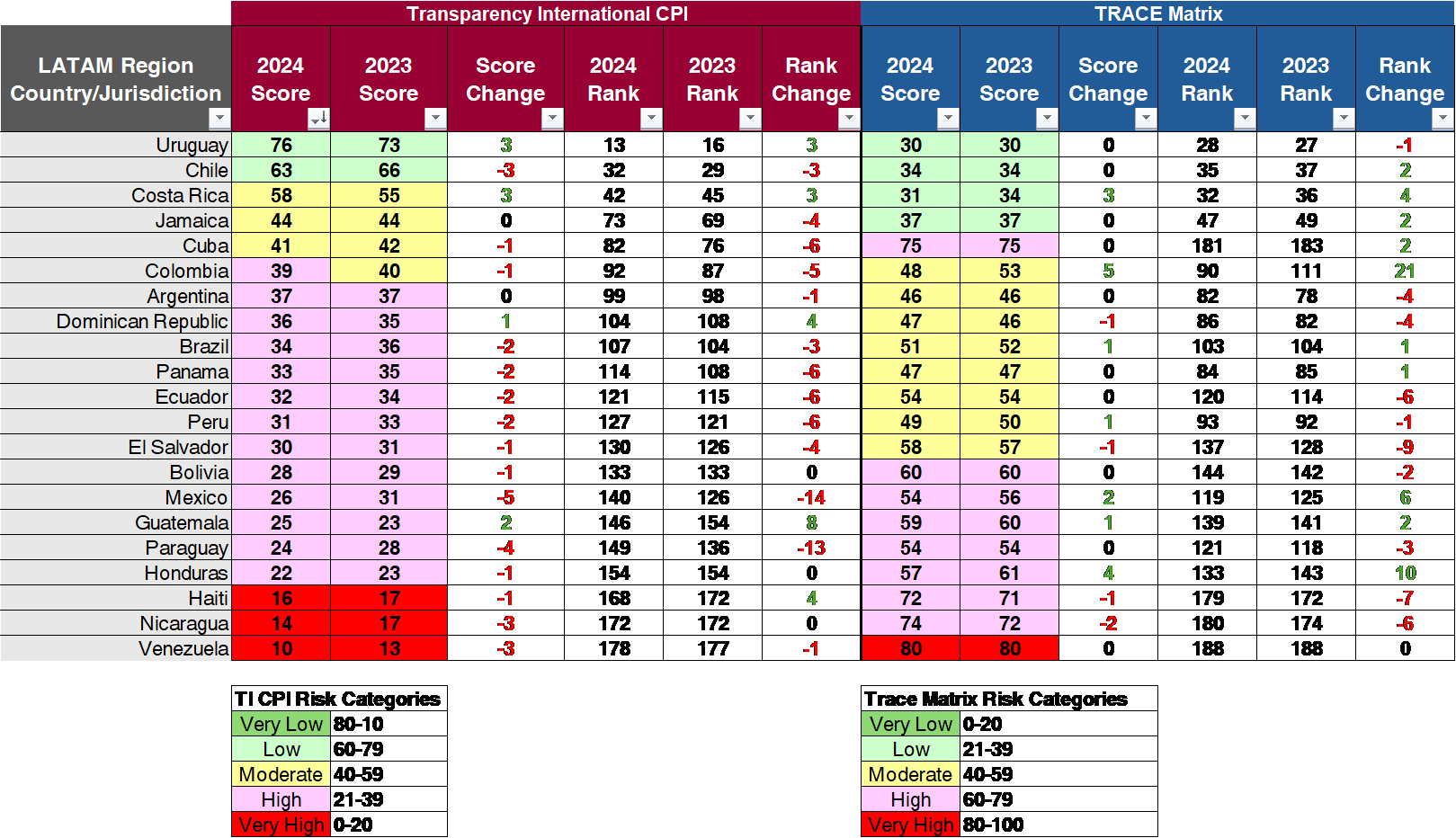

In 2024, bribery and corruption risks in Latin American (LATAM) countries remained above the global average, according to two important corruption indices: Transparency International's 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) and TRACE's 2024 Bribery Risk Matrix (Matrix). These indices employ different methodologies and scoring systems and, when viewed together, provide a useful window into the corruption risk present in particular geographies.

The CPI’s regional average score for LATAM was 34, indicating a high risk. The CPI's data shows that more than two-thirds of the countries in the region are perceived as being high to very high risk for bribery and corruption. In contrast, the Matrix indicates that fewer than half of the countries in LATAM fall into the high to very high-risk categories.

Approximately two-thirds of the countries in the LATAM region declined in their CPI scores, and most saw their rankings drop as well. Notably, Mexico dropped five points in its score and fell 14 places in the ranking. Conversely, Uruguay gained three points and jumped three places on the CPI, securing the 13th spot in the global ranking and making it the highest-ranked country in Latin America.

Overall, the scores on the Matrix risk scale remained stable, with no countries shifting into a different risk category.

The chart below reveals some directional inconsistencies. For instance, Colombia's CPI score decreased by one point, and it fell five positions in the CPI rank. However, Colombia significantly improved on the Matrix, with a five-point score increase and a staggering rise of 21 places in the rankings. Similar discrepancies were seen for Uruguay, Chile, Jamaica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Panama, Peru, Mexico, and Honduras due to differing CPI and Matrix methodologies.

Enforcement Policy Context

Many readers are likely aware that the US Department of Justice (DOJ) has temporarily paused enforcement of the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) for a period of six months. This pause is subject only to exceptions approved by the US Attorney General and is set to end in July 2025, although it could be extended. However, even if the US chooses not to rigorously enforce the FCPA during this presidential term, it is important to note that this term is shorter than the applicable statute of limitations. In addition, given the tenor and substance of other current administration policies, we expect that non-US companies may continue to face enforcement risk, particularly those headquartered in LATAM, which may be of particular interest to the current DOJ.

Further, other countries have not implemented a similar "pause." In fact, UK, France, and Switzerland authorities recently announced the formation of an International Anti-Corruption Prosecution Task Force to strengthen collaboration through information sharing, cooperative investigation strategies, and other methods to enforce their anti-bribery legislation. All three countries have wide-reaching statutes conferring jurisdiction to prosecute overseas bribery if there is a link to the prosecuting country. In LATAM, while the enforcement of anti-corruption laws has been mixed, there are countries where authorities have actively sought to increase enforcement in recent years. From our experience and discussions with compliance professionals, it is evident that companies are wisely choosing not to "pause" their anti-corruption compliance programs.

Corruption Index Methodologies

Both the CPI and the Matrix score countries between 1 and 100, ranking them accordingly. On the CPI, a higher score means lower risk, while on the Matrix, a higher score indicates higher risk. For example, North Korea, the country with the highest risk on both tools, ranks 170th on the CPI with a score of 15 but ranks 194th on the Matrix with a score of 92.

The CPI assesses public corruption perceptions based on 13 data sources and excludes certain factors such as private sector corruption, financial secrecy, and transnational corruption. In contrast, the Matrix evaluates both public and commercial risks, incorporating a wider array of information beyond mere perceptions. It scores four key corruption indicators: the opportunity for bribery (government interaction, expectation, and leverage), deterrence (dissuasion and enforcement), transparency (government and civil service), and oversight (free press and civil society). This comprehensive approach provides a nuanced understanding of corruption dynamics.

Jurisdictions of Note

Argentina maintained the same CPI score as in 2023 but dropped one position in its ranking. However, it fell four places in the Matrix ranking without changing its score. Transparency International referred critically to Argentina’s new decree, which limits public access to information, highlighting that responses from the executive branch to requests for information decreased in both quantity and quality.

Brazil declined two points in its CPI score and moved three positions down in the ranking. However, it improved on the Matrix, gaining one point and advancing one position. Last year, a justice of the Brazilian Supreme Court remarkably annulled all evidence from a settlement reached by Odebrecht (now Novonor) in connection with the Operation Carwash scandal. In February 2024, this justice also suspended payment of the R$ 8.5 billion (approximately US$ 1.5 billion) fine imposed on the company as part of that settlement. Interestingly, Transparency International has itself been a target of criticism in Brazil, reflecting the controversy surrounding the Operation Carwash prosecutions in recent years. This same justice ordered a criminal investigation against TI based on allegations that Brazilian prosecutors illegally directed funds from settlement agreements to that organization. In October 2024, however, the Office of the Attorney General requested termination of the investigation, contending that the allegations were unsubstantiated.

Chile's CPI score decreased by three points, and its rank dropped three positions. Nevertheless, Chile continues to be perceived as the second least corrupt country in Latin America, following Uruguay. In contrast, it kept the same Matrix score and rose two positions in the global ranking. In December 2023, Chile adopted the National Strategy on Public Integrity for the years 2023-2033. This public policy aims to enhance standards of transparency and integrity across five key pillars:1) civil service, 2) public resources, 3) transparency, 4) politics, and 5) the private sector. This strategy outlines specific objectives, such as the creation of a national registry of the beneficial owners of legal persons, investment funds, and other unincorporated entities to facilitate the detection of fraud, money laundering, terrorist financing and organized crime activities.

Colombia lost one point in its CPI score and dropped five positions in the rankings. In contrast, Colombia's standard improved on the Matrix, gaining five points and 21 notches in its ranking. In March 2024, Colombia issued Decree 390 of 2024, which regulates the procedure for granting leniency in instances of transnational bribery and corruption. The leniency program allows full or partial immunity from penalties for companies that provide relevant and useful information about the misconduct and disclose the benefits obtained.

Mexico dropped five points in its CPI score and 14 positions in its ranking. Conversely, it gained two points and advanced six positions in the Matrix. In September 2024, Mexico's Congress passed a controversial judicial reform law that mandates the election of its judiciary, including Supreme Court justices, by popular vote. The change raises concern about the independence of Mexican courts and the checks and balances set forth by the Mexican constitution.

Peru lost two points in its CPI score and dropped six positions in its ranking, while its Matrix score increased by one point and lost one position. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has expressed concern about undue interference from Congress and political leaders with the operations of the National Board of the Judiciary, the National Electoral Court, and the offices of public prosecutors in charge of investigating corruption cases in Peru. This interference is perceived to be a violation of constitutional checks and balances and a factor contributing to the ongoing deterioration of democracy in Peru.

Conclusion

The CPI's assessment of corruption risk shows deteriorating conditions in the LATAM region, as evidenced by lower scores overall and most countries dropping in the rankings. In contrast, the Matrix assessment presents a more nuanced view, showing some countries making improvements. These differences likely come from variances in the tools' methodologies. To effectively tackle the ongoing issue of corruption in several key markets within LATAM, it is essential for companies operating in the region to implement robust compliance programs.