Overview

Overview

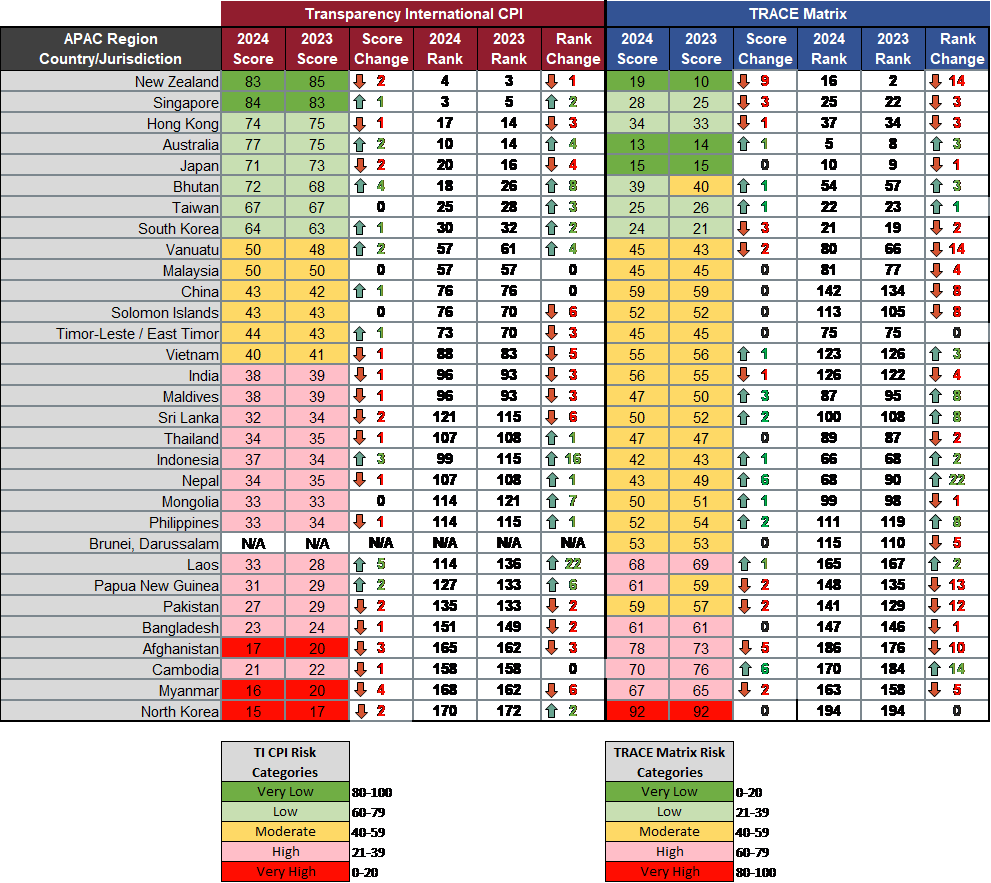

In 2024, bribery and corruption risks in Asia-Pacific (APAC) countries remained above the global average, underscoring significant challenges in the region. This insight is derived from two key anti-corruption tools: Transparency International's 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) and TRACE's 2024 Bribery Risk Matrix (Matrix). Historically, these two tools have provided largely consistent results; however, their differing methodologies and scoring systems reveal some disparate findings. When viewed together, they provide a valuable overview of the complex risks and opportunities within the APAC region. It is important to note that neither tool assesses risks related to depositing or managing assets obtained through corrupt practices. This aspect is critical for evaluating transparency, deterrence, and accountability in anti-corruption analysis. Thus, compliance managers should not rely solely on these tools to determine the level of risk in operating in certain APAC countries.

Overall, the regional average score for both the CPI and the Matrix was 44. Interestingly, however, the CPI shows that more than half of the countries in the region are perceived as being at high- to very high-risk for bribery and corruption. In contrast, the Matrix indicates that less than a quarter of the countries in APAC fall into the high- to very high-risk categories. The 2024 CPI is available at https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024, while the 2024 Matrix publication packet is available at https://www.traceinternational.org/trace-matrix.

Additionally, we should note that the US Department of Justice's "pause" on enforcement of the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) under this administration is unlikely to apply to non-US companies. This pause is also temporary, lasting four years, which is shorter than the applicable statute of limitations, and does not impact other countries’ enforcement of their strong anti-corruption and anti-bribery laws. Consequently, companies contemplating a similar "pause" of their anti-corruption due diligence programs should carefully consider their potential risks in doing so.

Summary

Approximately one-third of the countries in the APAC region improved their scores, and nearly all of them also saw rising in rankings. Notably, Laos achieved the largest score increase, gaining 5 points and jumping 22 places on the CPI. Conversely, New Zealand, which was previously ranked second globally on the Matrix, dropped by 9 points in its score and fell 14 places in the rankings.

Overall, the risk scale remained mostly stable, with only two countries shifting into a new risk scale on the Matrix. Bhutan improved from moderate to low risk, increasing by 1 point and rising 3 places. In contrast, Papua New Guinea shifted from moderate to high risk, declining by 2 points and dropping 13 places.

The chart below reveals some directional inconsistencies. For instance, Cambodia’s CPI score decreased by 1 point, resulting in no change to its CPI rank. However, it significantly improved on the Matrix with a 6-point score increase and a rise of 14 places in rankings. Similar discrepancies were seen for Singapore, South Korea, Vanuatu, Vietnam, Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Papua New Guinea due to differing CPI and Matrix methodologies.

Methodologies

Both the CPI and the Matrix score countries between 1 and 100 and rank them accordingly. On the CPI, a higher score means lower risk, while on the Matrix, a higher score indicates higher risk. For example, North Korea, the country with the highest risk of both tools, ranks 170th on the CPI with a score of 15 but ranks 194th on the Matrix with a score of 92.

The CPI assesses public corruption perceptions based on 13 data sources and excludes certain factors like private sector corruption, financial secrecy, or transnational corruption. In contrast, the Matrix evaluates both public and commercial risks, incorporating a wider array of information beyond mere perceptions. It scores four key corruption indicators: the opportunity for bribery (government interaction, expectation, and leverage), deterrence (dissuasion and enforcement), transparency (government and civil service), and oversight (free press and civil society). This comprehensive approach offers a nuanced understanding of corruption dynamics.

Other Jurisdictions of Note

China improved its CPI scores by 1 point, with no change in its CPI ranking. However, it fell 8 places in the Matrix rankings, landing at the higher end of the moderate risk range, with no change in its Matrix score. On December 29, 2023, China’s legislature amended the criminal law to increase penalties for bribery and expand the scope to include private companies. Following this legislative strengthening, there has been increased scrutiny of corruption in the medical sector. Notably, in October 2023, the Intermediate People’s Court of Guangzhou issued the first public conviction for the bribery of foreign public officials to secure business advantages.

Singapore saw an improvement on the CPI, gaining 1 point and moving up 2 ranks, becoming the least corrupt APAC country with a global ranking of 3rd. However, it declined on the Matrix, dropping 3 points and 3 ranks. This discrepancy likely stems from the CPI’s exclusion of private-sector corruption, which accounted for 86% of cases investigated in 2023.

South Korea also improved on the CPI, gaining 1 point and moving up 2 ranks. The CPI highlighted the efforts of young activists for leading "a four-year legal battle" that has successfully raised environmental awareness before the Constitutional Court. Nevertheless, it declined slightly on the Matrix, down 3 points and 2 ranks. This decline is likely due to insufficient "lobbying for [] regulation or implementation" and the lack of "centralised data currently available to fully monitor [conflict of interest] declarations" among public officials.

Japan saw declines on both the CPI, dropping 2 points and 4 ranks, and the Matrix, which remained unchanged but also fell 1 rank. In early 2024, Japan amended its foreign bribery laws and updated foreign bribery guidelines. However, this progress was overshadowed by bribery cases involving Japanese officials. This year, Japan was implicated in a settlement with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and US Department of Justice (DOJ) after a cryptocurrency mining company bribed various foreign officials, including members of Japan’s parliament, in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to establish a resort casino.

India experienced a decline on both the CPI, down 1 point and 3 ranks, and Matrix, down 1 point and 4 ranks. While score changes of one or two points are statistically insignificant, India claimed the top spot globally for FCPA enforcement in 2024 due to implications in two FCPA matters. The CPI specifically highlighted one ongoing investigation involving over US$250 million in bribes paid to Indian government officials for securing solar energy contracts.

Indonesia improved on both the CPI, gaining 3 points and rising 16 ranks, as well as on the Matrix, with a gain of 1 point and 2 ranks. However, the significant rise in CPI ranks does not reflect a real advancement in Indonesia’s anti-corruption efforts; rather, it resulted from a methodological change. The CPI reintroduced a source "from the World Economic Forum [] that had not been used in the index calculation in 2022 and 2023." The CPI also flagged Indonesia as "full of examples" of corruption in the energy sector.

Vietnam experienced a slight decline in the CPI, down 1 point and 5 ranks, due to "systemic corruption…from lower level to high-ranking public officials, [leading to] environmental destruction and forest degradation." In contrast, it improved on the Matrix, gaining 1 point and 3 ranks, likely due to the methodological differences. Since the initiation of its “blazing furnace” anti-corruption campaign in 2016, Vietnam’s CPI scores have risen by 7 points (from 33 in 2016 to 40 in 2024), and its Matrix scores have improved by 22 points (from 77 to 55). Remarkably, in April 2024, a Vietnamese billionaire was sentenced to death for her involvement in what is “arguably the largest corruption scandal in Southeast Asian history," leading to the prosecution of 24 government officials and the investigation of 23 state officials.

Philippines declined 1 point in its CPI scores but improved its rankings by 1 place. It also improved on the Matrix, gaining 1 point and advancing 8 ranks. Although the 1-point changes on both tools are insignificant and do not reflect stronger or weaker governance, the Philippines continues to fall significantly below the average CPI scores for the APAC region. In 2024, the Philippines was implicated in a case involving US$1 million in bribes paid to the former chairman of an independent agency overseeing election laws. This aimed to secure three contracts worth US$182 million for voting machines during the 2016 elections.

Thailand showed minimal changes across both tools, with its CPI score decreasing by 1 point while improving 1 rank. The Matrix scores remain unchanged, but the country dropped 2 ranks. Like the Philippines, Thailand's scores are significantly below the CPI's APAC average. According to an Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report, Thai authorities have been ineffective in enforcing anti-bribery laws, both domestically and internationally. In fact, within the private sector, including 7 of Thailand’s top 50 companies, the OECD found a prevalent belief that "in practice businesses may ignore [foreign bribery risks] for the sake of profit." This sentiment is further illustrated by a 2024 SEC settlement of nearly US$10 million, which involved bribes paid to various Thai government officials to secure business contracts.

Conclusion

The CPI’s and Matrix’s assessments of corruption risk in the APAC region show stable or improved scores, reflecting incremental progress in combating corruption and enhancing challenges. However, persistent declines underscore ongoing governance challenges. These risks pose a continuing challenge for compliance measures, especially as it is yet unknown whether APAC countries will step up their enforcement as a result of the US FCPA pause. Robust compliance frameworks promoting integrity and transparency are becoming increasingly critical, serving as the foundation for sustainable development and societal trust.